When a brand-name drug loses its patent, the market doesn’t just get cheaper-it gets messy. You’d think that if five, ten, or even twenty companies start making the same pill, prices would plummet. And sometimes, they do. But other times, prices barely budge. Why? Because in the world of generic drugs, more competitors don’t always mean lower prices. The real story is about strategy, regulation, and hidden power plays between manufacturers, insurers, and regulators.

The Myth of Perfect Competition

The textbook model says: more sellers = lower prices. In generic drug markets, that’s only half true. The FDA found that when the first generic enters the market, prices drop 30-39% compared to the brand. With two generics, that jump to 54%. By the time six or more companies are selling the same drug, the average manufacturer price (AMP) falls by 95%. Sounds great, right? But here’s the catch: that 95% drop rarely happens in practice. Most drugs never get past two or three generic makers. A 2023 study of 27 originator drugs in China showed that 70% still had only one or two generic competitors eight quarters after the first generic hit the market. Why? Because entering the generic drug business isn’t like opening a lemonade stand. It’s expensive, slow, and full of legal traps.Complex Drugs Block New Entrants

Not all drugs are created equal. A simple tablet like metformin? Easy to copy. A complex injectable, a patch that releases medicine over days, or a capsule with special coatings? Not so much. These are called “complex generics.” To prove they’re the same as the brand, manufacturers must pass three levels of testing: Q1 (same ingredients), Q2 (same physical properties), and Q3 (same performance in the body). Each test costs millions. Only the biggest generic companies-like Teva, Mylan, or Sandoz-can afford it. That means even if the FDA approves 10 generic versions of a complex drug, only 2 or 3 actually make it to market. The rest get scared off by the cost and risk. So instead of a crowded field, you get a quiet oligopoly. And when there are only a few players, they don’t fight each other. They just match prices.Mutual Forbearance: When Competitors Don’t Compete

Here’s the strangest part: sometimes, generic companies act like they’re in cahoots. Researchers in Portugal studied statins-cholesterol drugs-and found something shocking. Even though six different generics were on the market, prices stayed near the government’s price cap. Why? Because each company knew that if they lowered their price, the others would follow. No one wins. So they all just stayed at the ceiling. This is called “mutual forbearance.” It’s not collusion. It’s not illegal. It’s just smart business in a regulated system. When regulators set price caps, they accidentally create a floor for competition. Companies stop trying to undercut each other because there’s no point. The result? Patients get generics, but they don’t get cheaper ones.

Brand Companies Fight Back

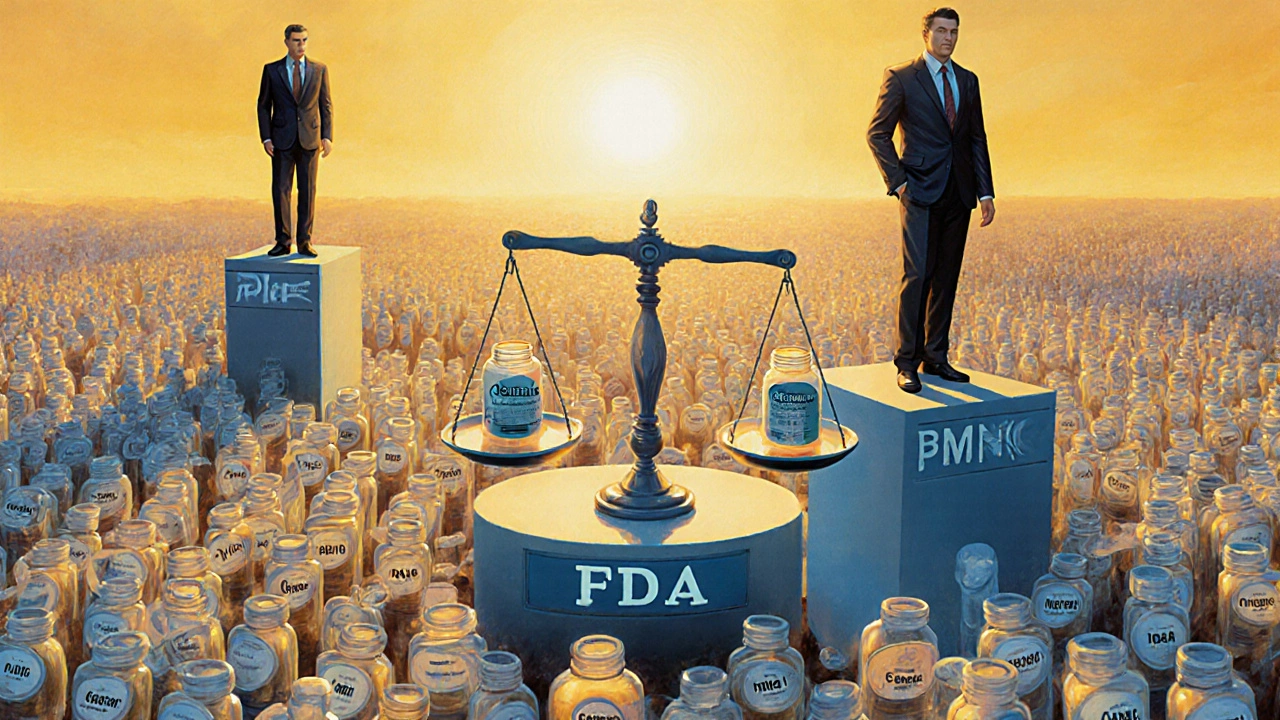

It’s not just generics playing games. The original drug makers fight too. In the same Chinese study, 24 brand companies lowered their prices by 3% after generics entered. But 3 of them actually raised prices. How? By marketing their brand as “better,” “more reliable,” or “preferred by doctors.” Even if the pills are chemically identical, patients and doctors sometimes trust the name they’ve known for years. And then there’s the authorized generic-a sneaky trick. The brand company itself launches a generic version during its 180-day exclusivity window. It’s the same drug, same factory, same packaging-just without the brand name. This crushes independent generics by stealing their market share before they even get started. But here’s the twist: when the authorized generic is owned by a different company, brand prices end up 22% higher. Why? Because the original maker feels less pressure to cut prices when they’re not the ones selling the cheap version.Who Really Controls the Market?

You might think pharmacies or patients set prices. But in the U.S., it’s Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs). These middlemen negotiate drug prices between manufacturers and insurers. In 2017, they handled 90% of all drug purchases. That means a drug’s price isn’t just about competition-it’s about who’s doing the negotiating. PBMs care about rebates, not list prices. So a brand drug might charge $100, but offer a $60 rebate to the PBM. A generic charges $20 with no rebate. The PBM still makes more money pushing the brand. So even if generics are cheaper, they don’t always get prescribed. That’s why, despite being 90% of prescriptions, generics only make up 23% of total drug spending.Supply Chain Safety: Why More Competitors Matter

Even when prices don’t drop, having multiple generic makers saves lives. Between 2018 and 2022, drugs with three or more manufacturers had 67% fewer shortages than those made by just one company. Why? Because if one factory shuts down, another can step in. If one company goes bankrupt, others keep producing. That’s why the FDA warns that new price controls-like the Inflation Reduction Act’s Maximum Fair Prices for Medicare drugs-could backfire. If a drug’s price is capped too low, generic makers won’t make enough profit to stay in business. That means fewer competitors over time. And fewer competitors means more shortages. And shortages mean patients can’t get their medicine.

Global Differences: What Works Elsewhere?

The U.S. isn’t the only player. In Europe, governments set prices directly through centralized negotiations. In countries like Germany or the UK, the government decides what a drug is worth-and companies have to accept it. That leads to lower prices, but also slower generic entry. In Portugal, price caps created mutual forbearance. In Canada, reference pricing (linking prices to other countries) pushes companies to compete globally. There’s no one-size-fits-all solution. What works in one country can backfire in another. The key is understanding that competition isn’t just about the number of companies-it’s about the rules they play by.The Future: Biosimilars and Digital Tools

The next wave of competition isn’t small-molecule generics anymore. It’s biosimilars-copies of complex biologic drugs like Humira or Enbrel. These aren’t pills. They’re living drugs made from cells. Developing them costs hundreds of millions. So far, only a handful of biosimilars have entered the market. And their price cuts? Only 15-30%, not the 85% seen with traditional generics. FDA Commissioner Robert Califf says this is the new frontier. Digital tools might help. AI can predict which drugs are likely to face shortages. Blockchain could track supply chains. But without real competition, none of that matters.What Really Drives Generic Drug Prices?

Let’s cut through the noise. The price of a generic drug isn’t determined by how many companies make it. It’s determined by:- Drug complexity: Simple pills = more competition. Complex drugs = fewer players.

- Regulatory rules: Price caps? They stop competition. Open bidding? They encourage it.

- Market power: PBMs, brand companies, and authorized generics can all block true competition.

- Supply chain needs: More makers = fewer shortages. That’s worth more than a few cents off a prescription.

Why don’t generic drug prices drop even when there are many competitors?

Prices don’t always drop because of market structure, not just competitor count. Complex drugs deter small manufacturers, price caps limit how low prices can go, and companies sometimes avoid undercutting each other to maintain profits-known as mutual forbearance. Also, Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs) often favor branded drugs with rebates, reducing pressure on generics to lower prices.

Do authorized generics hurt independent generic manufacturers?

Yes. When the original brand company launches its own generic version during the 180-day exclusivity window, it captures most of the market before other generics can scale. Independent manufacturers lose their window to build customer trust and distribution. This tactic, called “authorized generic entry,” reduces competition and can delay price drops.

Why do some brand-name drugs raise prices after generics enter the market?

Some brand companies raise prices to compensate for lost market share, especially if their drug has a reputation for reliability or if patients and doctors prefer the brand. This is more common with drugs used for chronic conditions where switching isn’t easy. In China, 3 out of 27 originator drugs actually increased prices after generic entry, showing that brand loyalty can override cost concerns.

How do regulatory price caps affect generic competition?

Price caps can unintentionally reduce competition. When governments set a maximum price, companies have less incentive to undercut each other. In Portugal, this led to “mutual forbearance,” where all generic makers priced near the cap instead of competing on price. This stabilizes revenue but keeps prices higher than they’d be in a free market.

Why is having multiple manufacturers important for drug supply?

Multiple manufacturers reduce the risk of shortages. If one company shuts down a factory, faces a recall, or goes bankrupt, others can keep supplying the drug. FDA data shows drugs with three or more manufacturers had 67% fewer shortages between 2018 and 2022. This resilience matters more than a few cents in price savings.

Will the Inflation Reduction Act hurt generic drug competition?

It might. The Act’s Maximum Fair Prices for Medicare drugs could make it unprofitable for generic manufacturers to produce certain drugs, especially complex ones. If companies can’t earn enough to cover costs, they’ll exit the market. Fewer competitors mean higher risk of shortages and less pressure to drive down prices long-term.

Are biosimilars the future of generic competition?

They’re the next phase, but not a direct replacement. Biosimilars are copies of biologic drugs-complex proteins made from living cells. They cost far more to develop than traditional generics, so price reductions are smaller (15-30% vs. 85%). They face similar barriers: high development costs, regulatory hurdles, and brand loyalty. True competition here will require new policies, not just more companies.

Kihya Beitz

November 14, 2025 AT 14:23So let me get this straight-we spend billions on drugs, and the only thing that’s actually ‘generic’ is the profit margin? 😒

Meanwhile, my insulin costs more than my rent and I’m supposed to be grateful because ‘there’s competition’? Nah. This isn’t capitalism. It’s a rigged board game where the players all have the same cheat code.

And PBMs? More like ‘Profit-Benefit Manipulators.’ They’re the middlemen who make money off your suffering. Thanks, America.

Also, ‘authorized generics’? That’s like McDonald’s opening a new location called ‘Burger King’ and then pretending it’s not them. 🤡

Jennifer Walton

November 15, 2025 AT 11:33Competition without freedom is just performance art.

The market isn’t broken-it was designed this way.

More players ≠ more choice. Just more actors in the same script.

ASHISH TURAN

November 15, 2025 AT 23:52Interesting how complexity becomes a barrier, not a feature. In India, we see this with cancer meds-small labs try, but the testing costs are insane. Many fold before even starting.

It’s not just about money-it’s about trust. Doctors stick with what they know, even if it’s more expensive.

And yes, PBMs are the real puppeteers. No one talks about them, but they control everything.

Maybe the solution isn’t more generics-it’s more transparency. Let patients see the real cost, not the sticker price.

Ryan Airey

November 17, 2025 AT 17:34This whole system is a joke. You call this ‘competition’? It’s a cartel with a FDA stamp.

Brand companies launch their own generics to kill the real ones? That’s not innovation-that’s corporate murder.

And now the government wants to cap prices? Great. Now the only ones left will be the big pharma subsidiaries. More monopoly, less choice.

Stop pretending this is about patients. It’s about shareholders.

Hollis Hollywood

November 17, 2025 AT 18:26I’ve been thinking about this for weeks, and honestly, it breaks my heart. People don’t realize that when a drug goes generic, it’s not just about price-it’s about survival.

My mom had to switch to a generic statin after her insurance changed. She panicked. Thought it wouldn’t work. She cried. It wasn’t about cost-it was about fear.

And then there’s the shortage risk. One factory fails, and someone’s life is on hold. That’s not a business problem. That’s a moral one.

I wish we could see the faces behind these numbers. The workers in the plants. The nurses who scramble to find meds. The kids who miss school because their dad can’t afford his heart pill.

Maybe the real question isn’t ‘why don’t prices drop?’ but ‘why don’t we care enough to fix it?’

Aidan McCord-Amasis

November 19, 2025 AT 07:13More generics = more chaos. 😅

Also, PBMs are the real villains. 💸

Also, authorized generics are the ultimate flex. 🤡

Adam Dille

November 19, 2025 AT 12:48There’s something beautiful about how complex this is. It’s not just economics-it’s psychology, trust, regulation, and human behavior all tangled up.

People think ‘more competition’ is the fix, but sometimes, too many players just creates paralysis. Like when 10 people try to cook a meal together and no one knows who’s in charge.

Maybe we need fewer, but better-regulated competitors. Ones that can actually survive without being crushed by costs or middlemen.

And yeah, PBMs are wild. Imagine if your grocery store negotiated your food prices and got paid based on how much you spent on expensive brands. That’s PBMs.

I’m not saying we need to go full Europe, but maybe we can learn something from how other countries balance cost, access, and innovation.

Katie Baker

November 20, 2025 AT 06:53Thank you for writing this. It’s so easy to just say ‘generic = cheaper’ and move on. But the reality is so much messier-and way more important.

Having multiple manufacturers isn’t just about price. It’s about safety. It’s about not having a whole country go without insulin because one factory had a bad batch.

I hope more people read this. We need to stop treating medicine like a commodity and start treating it like a right.

And yes, PBMs need to be called out. They’re the invisible hand that’s actually squeezing our throats.

John Foster

November 21, 2025 AT 13:48Let’s not pretend this is about healthcare. It’s about power. The power of capital to control life itself.

The FDA, the PBMs, the brand companies-they’re not separate entities. They’re a single organism. A machine designed to extract value from human vulnerability.

When a patient chooses a generic, they’re not choosing cost-they’re choosing trust. And trust, in this system, is manufactured. By marketing. By reputation. By fear.

The myth of perfect competition is the greatest lie in modern medicine. There is no perfect competition. There is only control disguised as choice.

And now, with price caps, we’re not fixing the system-we’re just making it more brittle. Because when profit disappears, so does production. And when production disappears, so do lives.

We are not building a healthcare system. We are building a death clock with a price tag.

Edward Ward

November 21, 2025 AT 23:13There’s an interesting paradox here: the more we try to regulate prices, the more we inadvertently protect the status quo.

Price caps, while well-intentioned, eliminate the incentive for new entrants to take the risk-especially for complex drugs. And since the barrier to entry is already so high, you end up with a shrinking pool of competitors.

Meanwhile, PBMs aren’t just middlemen-they’re gatekeepers. Their rebate-driven model actively disincentivizes the cheapest option. That’s not market efficiency-that’s market distortion.

And the authorized generic? It’s not just a tactic-it’s a weapon. It’s the brand company saying, ‘We don’t need to compete. We can just become the competition.’

What’s missing from this entire conversation is the patient’s voice. We talk about manufacturers, regulators, and PBMs-but who’s asking the people who actually swallow these pills what they need?

Maybe the real solution isn’t more competition. Maybe it’s more accountability. Transparency in pricing. Real oversight of PBMs. And a system where survival isn’t tied to profit margins.

Andrew Eppich

November 22, 2025 AT 07:11This article is fundamentally misguided. The free market is not broken. It is being sabotaged by government intervention.

Price controls are immoral. They punish innovation and reward laziness. If a company cannot compete, it should fail.

Patients should not be entitled to cheap drugs. They should be responsible for their own choices.

The fact that people expect medicine to be affordable is the real problem. This is not a right. It is a privilege earned through hard work and personal responsibility.

Stop blaming corporations. Start blaming the people who demand free stuff.

Jessica Chambers

November 22, 2025 AT 13:35So… we’re saying the system is designed to keep prices high, even when there are 10 companies making the same pill? 😑

And PBMs are the ones deciding what gets prescribed? Not doctors? Not patients?

That’s not capitalism. That’s a dystopian sitcom.

Also, authorized generics? That’s like if your landlord opened a competing apartment building right next door… and then rented it to your neighbors at the same price. 🤡