For decades, Africa relied on medicine shipped from halfway across the world to keep people alive with HIV. In 2000, a year of treatment cost more than $10,000. By 2015, thanks to Indian generics, that dropped to under $100. But even at that price, supply chains broke during pandemics, customs delays left clinics empty, and stockouts forced patients to go without. That changed on May 6, 2025, when the Global Fund delivered its first-ever shipment of African-made antiretroviral drugs to Mozambique. This wasn’t just another shipment-it was a turning point.

The TLD Breakthrough: Africa’s First WHO-Prequalified ARV

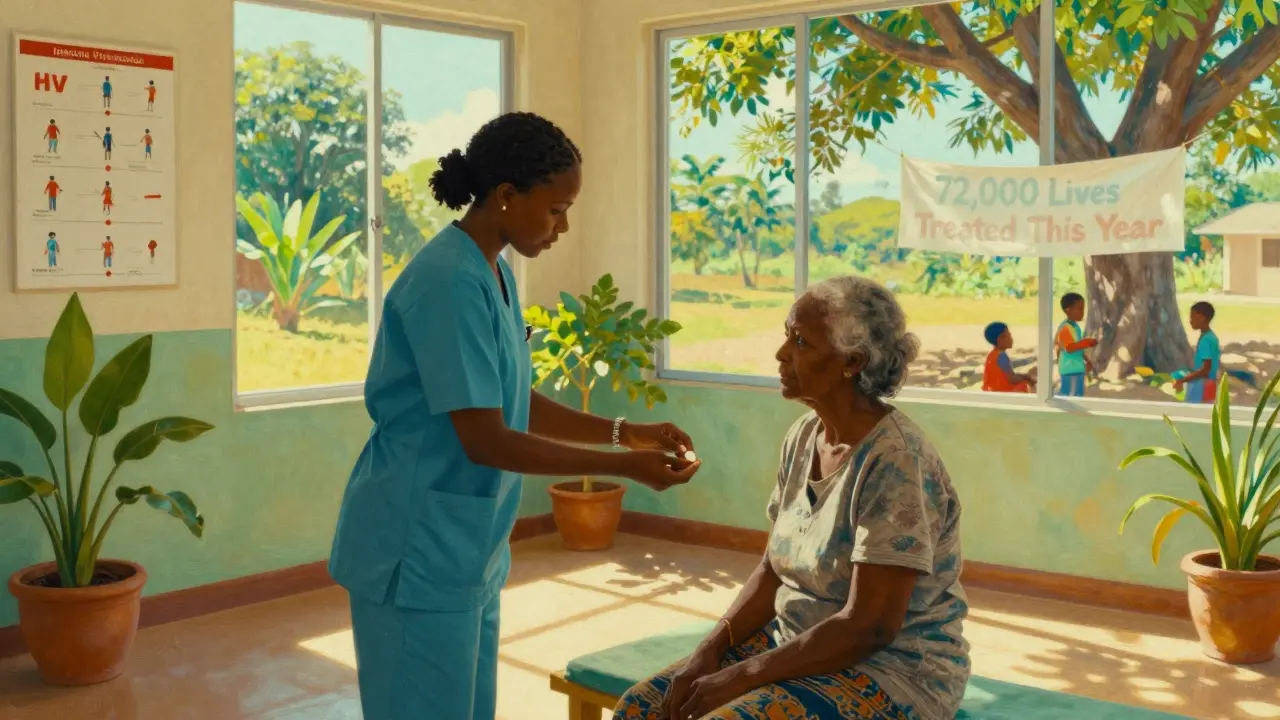

The drug? TLD: a single tablet combining tenofovir, lamivudine, and dolutegravir. It’s now the global gold standard for first-line HIV treatment. Why? Because it’s more effective, has fewer side effects, and makes drug resistance much harder to develop. Before 2023, no African company had ever passed the World Health Organization’s strict prequalification for TLD. Then, Universal Corporation Ltd in Kenya did. Their factory met the same quality standards as top European and U.S. labs. That meant the Global Fund could finally buy from Africa without risking safety or efficacy.The first order? Enough TLD to treat 72,000 people a year. That’s not the whole continent’s need-but it’s the first real step toward self-reliance. For the first time, African countries weren’t just recipients of aid. They were suppliers.

Why Local Production Matters More Than Cheap Imports

India made HIV drugs affordable. But affordability alone doesn’t fix broken systems. When COVID-19 hit, global supply chains froze. African nations waited months for basic medicines. Some clinics ran out of ARVs for over six weeks. Patients stopped taking pills. Viral loads rose. Transmission spiked.Local manufacturing solves this. When a country makes its own drugs, it doesn’t depend on shipping lanes, customs inspections, or foreign currency reserves. It can respond fast. If a new strain emerges, or a seasonal surge hits, local factories can ramp up production in weeks-not months.

And it’s not just about pills. Nigeria’s Codix Bio now makes HIV rapid tests under a WHO-backed technology transfer deal. South Africa registered the twice-yearly injectable cabotegravir in record time. These aren’t isolated wins. They’re pieces of a new system: diagnostics, treatment, and delivery-all built on African soil.

The Numbers Behind the Shift

Sub-Saharan Africa has 65% of the world’s HIV cases. Yet it produces less than 3% of its own medicines. That’s not sustainable. The continent needs about 15 million person-years of first-line ARVs every year. Right now, African manufacturers can cover maybe 5% of that.But that’s changing fast. New factories are coming online by the end of 2025. The Clinton Health Access Initiative predicts African-made ARVs could supply 20-30% of the continent’s needs by 2030-if funding and policy stay on track.

Progress is visible in the treatment cascade. In Eastern and Southern Africa, 93% of people with HIV know their status, 83% are on treatment, and 78% have suppressed viral loads. That’s up from 50% on treatment in 2010. In Western and Central Africa, those numbers are lower-81%, 76%, 70%-but they’re rising. Every percentage point means fewer deaths, fewer transmissions, and more lives lived fully.

Long-Acting Injectables and the Next Frontier

The future of HIV treatment isn’t just daily pills. It’s injections that last six months. South Africa became the first African country to approve the long-acting cabotegravir injection in October 2025. That’s huge. For people who struggle with daily pills-because of stigma, work schedules, or mental health-this is life-changing.Gilead Sciences licensed six African manufacturers to produce generic versions of this injection. Experts say prices could drop 80-90% below brand cost once generics flood the market. That’s not speculation. It’s what happened with TLD tablets. When Indian generics entered, prices fell from $10,000 to under $100. The same pattern is playing out now, but this time, African companies are leading the charge.

Even more promising: Gilead is giving away lenacapavir, a new long-acting PrEP drug, at no profit until generics arrive. They’re working with PEPFAR and the Global Fund to get it to 18 high-burden countries by the end of 2025. This isn’t charity. It’s strategy. They’re buying time for African manufacturers to build capacity-and ensuring no one gets left behind in the transition.

The Bigger Picture: Health Sovereignty, Not Just HIV

This isn’t just about HIV. It’s about building a health system that can handle the next pandemic, the next outbreak, the next crisis. Right now, Africa imports 80% of its medicines. That makes every country vulnerable. If a single factory in India shuts down, or a port closes, millions go without.The African Union’s Pharmaceutical Manufacturing Plan for Africa (PMPA) aims to raise local production from 3% to 40% by 2040. That’s ambitious. But it’s possible-if regulators harmonize standards, governments invest in training, and international partners keep funding.

It’s also about leadership. For too long, research on African health needs was done by outsiders. Now, African scientists are designing trials for local strains, tailoring formulations for regional diets, and training local pharmacists. This isn’t just manufacturing. It’s Africanizing medicine.

Challenges Still Standing in the Way

Progress isn’t automatic. Regulatory systems vary wildly between countries. Some lack the labs to test drug quality. Others don’t have the staff to manage complex supply chains. Financing is still patchy. Most new factories rely on grants from the Gates Foundation, Unitaid, or CIFF. Once that money runs out, will they survive?And then there’s the market. If African manufacturers produce 10 million doses but only 5 million are needed, they lose money. That’s why the Global Fund’s procurement strategy is so smart. They’re guaranteeing demand. They’re signing multi-year contracts. They’re telling manufacturers: “We’ll buy from you, if you meet the standard.” That gives them the confidence to invest in new equipment, hire engineers, train workers.

There’s also the issue of scale. One factory in Kenya can’t supply all of Africa. But five? Ten? That’s possible. And with six companies licensed to make the long-acting injection, the momentum is building.

What Comes Next?

The Global Fund’s Grant Cycle 7 (GC7) will announce its next round of eligible countries soon. That means more African-made ARVs heading to more clinics. More jobs. More local expertise. More control.This isn’t about replacing Indian generics. It’s about adding African ones to the mix. A diversified supply chain is a resilient one. And for a continent that’s lost too many lives to delays, shortages, and dependence-it’s not just smart. It’s necessary.

By 2030, a child born with HIV in Uganda might never need to wait for a shipment from abroad. Their treatment could come from a factory in Kampala, tested in a lab in Kigali, and delivered by a local health worker who lives down the street. That’s the future. And it’s already starting.

SWAPNIL SIDAM

January 25, 2026 AT 18:16Man, I remember when we had to wait 3 months for ARVs in Delhi. One box would get stuck at customs, and people would stop meds. This African move? It’s not just medicine-it’s dignity. 🙌

Sally Dalton

January 25, 2026 AT 20:13this is honestly one of the most hopeful things i’ve read all year. local production = less waiting, less fear, more control. i’m crying a little. 🥺

Mohammed Rizvi

January 26, 2026 AT 23:46India gave us the price drop. Africa’s giving us the future. And honestly? The way they’re handling long-acting injectables? That’s next-level strategy. No cap.

Skye Kooyman

January 28, 2026 AT 03:48So they’re finally making their own pills?

Faisal Mohamed

January 29, 2026 AT 05:41Let’s deconstruct the epistemology of pharmaceutical sovereignty: when agency is decoupled from colonial supply chains, the ontological status of ‘aid’ collapses into ‘partnership.’ TLD isn’t just a drug-it’s a postcolonial episteme manifest in tablet form. 🌍💊 #HealthSovereignty

eric fert

January 30, 2026 AT 08:15Look, I get the feel-good narrative-but let’s be real. Who’s paying for these factories? Gates Foundation? Unitaid? When the grants dry up, will these plants still be running? Or is this just another ‘African miracle’ built on sand? And don’t even get me started on how the Global Fund’s ‘guaranteed demand’ is really just a fancy subsidy with a flag on it. This isn’t independence-it’s dependency with a different logo.

Aishah Bango

January 31, 2026 AT 13:33It’s disgusting that it took this long. People died waiting for pills while Western pharma made billions. Now they want applause for doing the bare minimum? Wake up. This isn’t progress-it’s overdue justice. And if you’re celebrating it like it’s a gift, you’re part of the problem.

Uche Okoro

January 31, 2026 AT 15:03The structural inequities in global pharmaceutical governance remain unaddressed. The WHO prequalification framework, while ostensibly neutral, historically privileged Global North regulatory paradigms. African manufacturers now operating within this architecture are not merely producing drugs-they are performing epistemic resistance. The fact that Codix Bio passed scrutiny on par with Roche or GSK is a radical act of reclamation.

Curtis Younker

February 1, 2026 AT 12:58THIS IS THE FUTURE. Imagine a kid in Uganda getting their HIV meds from a factory 20 miles from home-no shipping delays, no customs drama, no waiting. That’s not just healthcare-that’s hope made physical. And the injectables? Game. Changer. Let’s get more funding. Let’s scale this. Let’s make sure no one else has to choose between rent and medicine. We can do this.

Peter Sharplin

February 1, 2026 AT 13:52One thing people miss: local production means local jobs. Pharmacists, lab techs, truck drivers, quality control staff-all African. That economic ripple effect is just as important as the pills themselves. And the tech transfer? Huge. Nigeria making tests, South Africa rolling out injections? That’s capacity building, not charity.

Napoleon Huere

February 2, 2026 AT 11:01There’s something poetic here. For decades, Africa was the patient. Now it’s the pharmacist. The lab. The manufacturer. The innovator. It’s not just about HIV-it’s about rewriting the story of who gets to heal, and who gets to be healed. The pill is just the载体. The real medicine is self-determination.

Robin Van Emous

February 3, 2026 AT 22:34It’s beautiful to see African scientists leading this. I’ve seen too many global health projects where outsiders design everything and leave. This time, it’s homegrown. And the fact that Gilead’s giving away lenacapavir while waiting for generics? That’s not just smart-it’s humble. We need more of that.

Ashley Porter

February 5, 2026 AT 08:51Let’s not romanticize this. Regulatory fragmentation across 54 countries is still a nightmare. One factory in Kenya can’t fix systemic gaps in Nigeria’s customs, or Ghana’s cold chain. The real challenge isn’t production-it’s coordination. And that’s the ugly, boring part nobody’s cheering about.