Anticoagulation Decision Tool

Personalized Anticoagulation Assessment

This tool helps determine the safest anticoagulant therapy for patients with both kidney and liver disease based on clinical parameters. Results are based on current guidelines and evidence.

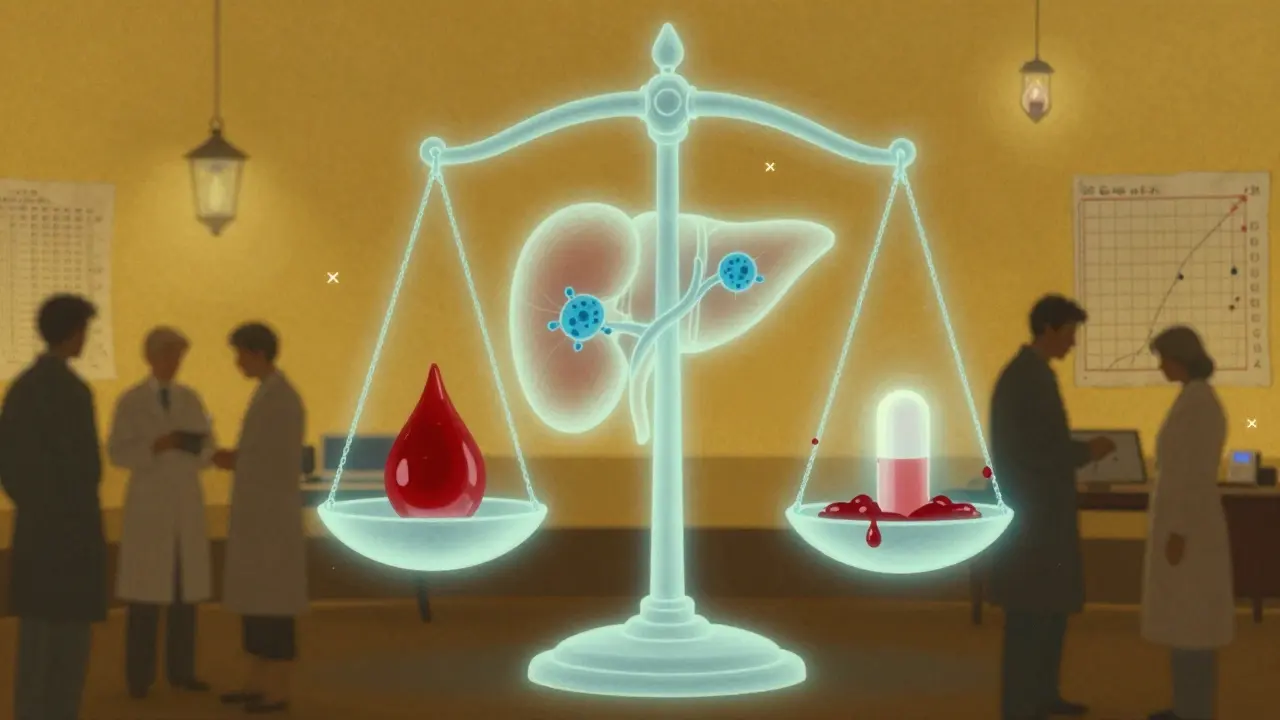

When someone has both kidney disease and liver disease, taking a blood thinner becomes one of the most dangerous balancing acts in medicine. It’s not just about avoiding clots - it’s about not bleeding to death. And yet, for millions of people, this decision is made with incomplete data, conflicting guidelines, and a lot of guesswork.

Why This Is So Hard

Most blood thinners were tested in healthy people. The big trials for newer drugs like apixaban, rivaroxaban, and dabigatran - called DOACs - left out patients with severe kidney or liver damage. That means we don’t have solid proof that these drugs work safely when both organs are failing. But we still need to treat people. Atrial fibrillation is common in both kidney and liver disease, and without anticoagulation, stroke risk jumps sharply. Yet, bleeding risk goes up even faster.Take kidney disease. The glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) tells us how well kidneys filter blood. But in advanced disease, even the best formulas get it wrong by 30-40%. A number like eGFR 28 might look like stage 4 CKD, but in reality, the person could be closer to stage 5. And if you’re on dialysis? The rules change again. Some doctors use apixaban at 2.5 mg twice daily. Others avoid it entirely. Why? Because while one study shows it cuts bleeding risk by 70% compared to warfarin, another found 2.8 times more stomach bleeds than warfarin in dialysis patients.

How Kidney Disease Changes the Game

Not all DOACs are created equal when kidneys fail. Dabigatran is 80% cleared by the kidneys - so if your eGFR drops below 30, it builds up like a clogged drain. That’s why it’s banned in advanced CKD. Rivaroxaban is 33% renal - still risky, and banned by Europe in stage 4-5 CKD. Apixaban is only 27% cleared by kidneys. That’s why it’s the only DOAC the FDA allows in stage 5, at half the normal dose. But even then, its levels in dialysis patients are about half of what’s seen in healthy people. Is that enough to prevent stroke? We don’t really know.Warfarin, the old-school blood thinner, doesn’t rely on kidneys. But it’s messy. INR targets? Usually 2.0-3.0. But in severe CKD, doctors often drop it to 1.8-2.5 because the blood clots more easily and bleeds more easily at the same time. Monitoring becomes a nightmare - you need INR checks every two weeks instead of monthly. And even then, the numbers jump around like a faulty thermometer.

Real-world data from 12,850 dialysis patients with atrial fibrillation shows something surprising: those on DOACs had fewer major bleeds than those on warfarin (14.2 vs 18.7 events per 100 patient-years). But stroke rates were nearly identical. So DOACs might be safer, but not necessarily better at preventing strokes. And 71% of these patients still got no anticoagulation at all - even though most had a high stroke risk score.

Liver Disease: The Hidden Danger

The liver doesn’t just process drugs - it makes clotting factors. In cirrhosis, the liver stops producing proteins that help blood clot, but also those that prevent clots. So patients are both more likely to bleed and more likely to clot. It’s a paradox. And the Child-Pugh score is the key to understanding risk.Child-Pugh A (mild disease)? DOACs can be used with standard doses. Child-Pugh B (moderate)? Proceed with caution. Child-Pugh C (severe)? Don’t use DOACs. Why? Because in one study, these patients had over five times the risk of major bleeding compared to those with healthy livers. And the INR? It’s useless here. The test only measures vitamin K-dependent factors, but in cirrhosis, platelets are low, fibrinogen is low, and clotting factors are all over the place. An INR of 1.8 might look normal - but the patient could be teetering on a hemorrhage.

Some hospitals now use thromboelastography (TEG) or rotational thromboelastometry (ROTEM) to get a full picture of clotting. But only 38% of U.S. hospitals have them. Most doctors are left guessing. One hepatologist told me he’s seen patients with platelets at 80,000 and INR at 1.5 - and still bled out after starting apixaban. Another had a patient with platelets at 45,000 and no bleeding on warfarin. There’s no formula. It’s experience.

DOACs vs Warfarin: The Real Trade-Offs

Here’s what the data says:| Factor | DOACs (Apixaban) | Warfarin |

|---|---|---|

| Renal clearance | 27% | 0% |

| Recommended in ESRD | Possible at 2.5 mg BID | Yes |

| Bleeding risk in CKD 4-5 | 31% lower than warfarin | Higher |

| INR reliability in cirrhosis | Not applicable | Unreliable (CV 42%) |

| Reversal agent available | Andexanet alfa (expensive, rare) | Vitamin K, PCC |

| INR target in CKD 4-5 | N/A | 1.8-2.5 |

Apixaban has the best safety profile in kidney disease. But in liver failure? Warfarin has a slight edge because we know how to reverse it. Andexanet alfa costs $19,000 per dose and is only in 45% of U.S. hospitals. Vitamin K and PCC? They’re cheap, widely available, and work - even if slowly.

What Doctors Are Actually Doing

In practice, most patients with advanced kidney and liver disease don’t get anticoagulation at all. Why? Fear. One nephrologist in Ohio told me: “I’d rather see a stroke than a bleed I couldn’t stop.” Another, in California, says: “I use apixaban 2.5 mg twice daily in every dialysis patient with AF - and I’ve had zero bleeds in 20 patients over three years.”Reddit threads are full of these contradictions. One user shared a case: a 72-year-old on dialysis with a history of GI bleeding. He was started on apixaban 2.5 mg daily. Three months later, he had a retroperitoneal hemorrhage. Another user described a 68-year-old with the same profile who’s been stable for five years on the same dose. No one knows why.

For liver disease, 68% of hepatologists report at least one major bleed in the past year linked to anticoagulation. Platelet counts matter more than INR. If platelets drop below 50,000, many stop treatment. If MELD score exceeds 20? That’s often the red line.

The Future: What’s Coming

Two major trials are underway. The MYD88 trial is comparing apixaban to warfarin in 500 dialysis patients - results expected in 2025. The LIVER-DOAC registry is tracking 1,200 cirrhotic patients on DOACs worldwide. These might finally give us answers.The FDA is also considering formal approval for apixaban in end-stage kidney disease. KDIGO, the global kidney health group, is preparing new guidelines in late 2024 - they’ll likely recommend apixaban as the only DOAC option in advanced CKD.

But until then, doctors are flying blind. And patients? They’re caught between the risk of stroke and the risk of dying from a bleed.

What You Need to Know

If you or someone you care for has both kidney and liver disease and needs a blood thinner:- Apixaban at 2.5 mg twice daily is the only DOAC with any real data in advanced kidney failure - and even then, it’s not proven.

- Warfarin is messy, but reversible. If you’re in a hospital with good monitoring, it might still be the safest bet.

- Don’t rely on INR alone in liver disease. Platelets, albumin, and MELD score matter more.

- Ask if your hospital has TEG or ROTEM. If not, ask if they have a nephrologist and hepatologist on call for anticoagulation decisions.

- Never assume a drug is safe just because it’s newer. The absence of evidence isn’t evidence of safety.

There are no easy answers. Only careful, individualized choices - and a lot of listening to the patient.

Can you use apixaban if you’re on dialysis?

Yes - but only at 2.5 mg twice daily, and only if there’s no other option. The FDA allows it based on post-hoc data showing lower bleeding risk than warfarin. However, no large trial has proven it prevents strokes in dialysis patients. Many doctors avoid it due to lack of outcome data, but some use it successfully with close monitoring.

Is warfarin better than DOACs in liver disease?

It depends. In Child-Pugh A, DOACs are fine. In Child-Pugh B, it’s a toss-up. In Child-Pugh C, warfarin is preferred - not because it’s safer, but because we know how to reverse it. DOACs can’t be reversed reliably in advanced cirrhosis, and bleeding is often fatal. But warfarin is harder to control - INR fluctuates wildly, and patients spend less time in the safe range.

Why is INR unreliable in cirrhosis?

INR only measures vitamin K-dependent clotting factors (II, VII, IX, X). In cirrhosis, patients also have low platelets, low fibrinogen, and low anticoagulant proteins like protein C and antithrombin. So an INR of 1.5 might look normal, but the patient’s blood may not clot at all. That’s why TEG and ROTEM - which test the whole clotting process - are better, but rarely available.

What if a patient has both severe kidney and liver disease?

This is the hardest scenario. Guidelines don’t cover it. Most experts avoid all anticoagulation unless the risk of clotting is extreme - like a recent portal vein clot. If anticoagulation is absolutely needed, apixaban 2.5 mg twice daily is the least risky option. But the decision must involve both a nephrologist and hepatologist. No single doctor should make this alone.

Are there any new blood thinners coming for these patients?

Not yet. The two major trials - MYD88 (for dialysis patients) and LIVER-DOAC (for cirrhosis) - are ongoing and won’t finish until 2025. Until then, we’re stuck with what we have. Some companies are developing kidney-sparing anticoagulants, but they’re still in early testing. For now, apixaban remains the best option we have - even if we’re not sure it’s the right one.

Mark Harris

February 8, 2026 AT 13:40Yo this post is fire. I work in ER and we see this every week - dialysis patients on apixaban, then come in with a retroperitoneal bleed and we’re scrambling. No one has a clear answer. I just tell families: ‘We’re winging it.’

Mayank Dobhal

February 9, 2026 AT 07:43Same. My uncle’s on dialysis. Doctor gave him apixaban 2.5mg BID. Three months later - GI bleed. Now he’s on aspirin. ‘Better than nothing’ they said. Lol. Aspirin doesn’t even work for AF. But hey, at least he’s not dead yet.

Ariel Edmisten

February 9, 2026 AT 14:01Aspirin isn’t even close to enough for AF. But in real life? Sometimes it’s the only choice left. I get it.

Patrick Jarillon

February 9, 2026 AT 22:38Let me guess - the pharmaceutical companies pushed DOACs because they’re $$$ and the FDA got lazy. No one tested them in real sick people because why bother? They made billions off healthy 50-year-olds with AFib. Meanwhile, the 72-year-old on dialysis? Just a footnote in a clinical trial appendix. This isn’t medicine. It’s capitalism with a stethoscope.

I’ve seen 12 patients in 6 months bleed out on apixaban. Every single one had an eGFR under 30. The guidelines? Written by guys who’ve never touched a dialysis machine.

And don’t even get me started on reversal agents. Andexanet costs more than a Tesla. Only 45 hospitals have it. So if you bleed? Good luck. Hope you live near a university hospital. Otherwise? You’re a statistic. The system doesn’t care. It’s designed to ignore you.

Warfarin? Messy? Yeah. But we’ve been using it for 70 years. We know how to fix it. Vitamin K. PCC. Cheap. Available. In every damn ER. But nooooo - we gotta chase the shiny new toy. Until someone dies. Then we say ‘oops.’

Someone needs to sue the FDA. And the makers of apixaban. And every damn guideline committee that says ‘it’s okay’ without data. This isn’t medical innovation. It’s negligence dressed in white coats.

Ritu Singh

February 10, 2026 AT 04:27Thank you for this deeply thoughtful and meticulously researched piece. It reflects the profound ethical tension inherent in modern clinical decision-making: the gap between evidence and practice. In many low-resource settings, we lack even basic INR monitoring - let alone TEG or ROTEM. The burden falls disproportionately on patients who are already marginalized. We must advocate not only for better data, but for equitable access to care. Knowledge without justice is merely intellectual luxury.

Savannah Edwards

February 11, 2026 AT 00:28I’ve been a nurse in nephrology for 14 years. I’ve seen patients on apixaban live for 5 years with zero bleeds. I’ve seen others bleed out within weeks. There’s no pattern. No biomarker. No score that tells you who’s safe. It’s like rolling dice while blindfolded.

One patient - 81, on dialysis, MELD 24, platelets at 48,000 - was started on apixaban 2.5mg BID because she had a stroke last year. She’s fine. No bleeding. Ever.

Another - 67, same numbers - bled into his abdomen after 10 days. He died. No warning. No labs screamed. Just… gone.

I’ve cried in the break room over this. Not because I made a mistake. But because there’s no right answer. We’re not gods. We’re just humans trying to do our best with broken tools.

I wish we had a crystal ball. But we don’t. So we listen. We talk. We adjust. We pray. And we hope.

And maybe… that’s the only medicine left.

Eric Knobelspiesse

February 12, 2026 AT 11:43ok so like… the whole DOAC thing is just a giant marketing scheme right? like warfarin is old but we know how to fix it. DOACs are new so they’re ‘better’ but no one actually tested them on people who are really sick. and now docs are scared to use warfarin because it’s ‘outdated’? lol. i work in a small hospital and we just use warfarin. i mean… if your INR is 1.8 and you’re on dialysis and your platelets are 50k… and you still bleed? maybe the problem isn’t the drug. maybe the problem is the whole system. also… why is andexanet so expensive? who’s making money here? just saying.

Catherine Wybourne

February 14, 2026 AT 03:22Oh honey. You think this is bad? Wait till you see what happens when someone’s on dialysis, has cirrhosis, and is also on chemo. Then we throw in a pulmonary embolism and say ‘pick your poison.’

My sister-in-law had all three. They tried apixaban. She bled. They switched to warfarin. She clotted. Then they stopped everything. Now she’s just… waiting. No treatment. No hope. Just a doctor saying ‘we did all we could.’

It’s not about guidelines. It’s about how much we care. And right now? We care more about lawsuits than lives.

AMIT JINDAL

February 14, 2026 AT 11:46OMG I’m a nephrologist in Mumbai and I’ve been doing this for 20 years 😭

Let me tell you - in India, we don’t even have TEG. Most hospitals don’t have dialysis machines that work reliably. We use apixaban 2.5mg BID because it’s the only thing we can afford. And guess what? We have LOWER bleeding rates than the US. Why? Because we don’t over-treat. We don’t chase perfect numbers. We just… give what we can. And sometimes? That’s enough.

Also - INR is useless in cirrhosis? DUH. We’ve known that since the 90s. But American guidelines? Still stuck in 2010. LOL. The West thinks they’re ahead. We’re just surviving. And honestly? We’re doing better.

Also - 71% of patients don’t get anticoagulation? That’s because we’re not pushing drugs. We’re pushing dignity. Sometimes… not treating is the most ethical choice.

Natasha Bhala

February 14, 2026 AT 13:53My dad had this. We chose warfarin. He’s been stable for 4 years. No bleeds. No strokes. Just weekly blood draws. It’s a hassle. But he’s here. And that’s all that matters.

Ashley Hutchins

February 15, 2026 AT 22:52Why do people keep using DOACs when they know the data is trash? This is why medicine is broken. You’re not a doctor if you don’t question the hype. If your patient bleeds, it’s on you. Not the guidelines. Not the FDA. YOU. You chose to follow the trend. Now you’re just another doctor who killed someone with kindness.

Lakisha Sarbah

February 17, 2026 AT 12:39I just want to say thank you to every nurse, doctor, and patient who’s navigating this mess with grace. There’s no playbook. But you’re still showing up. That counts more than any guideline.