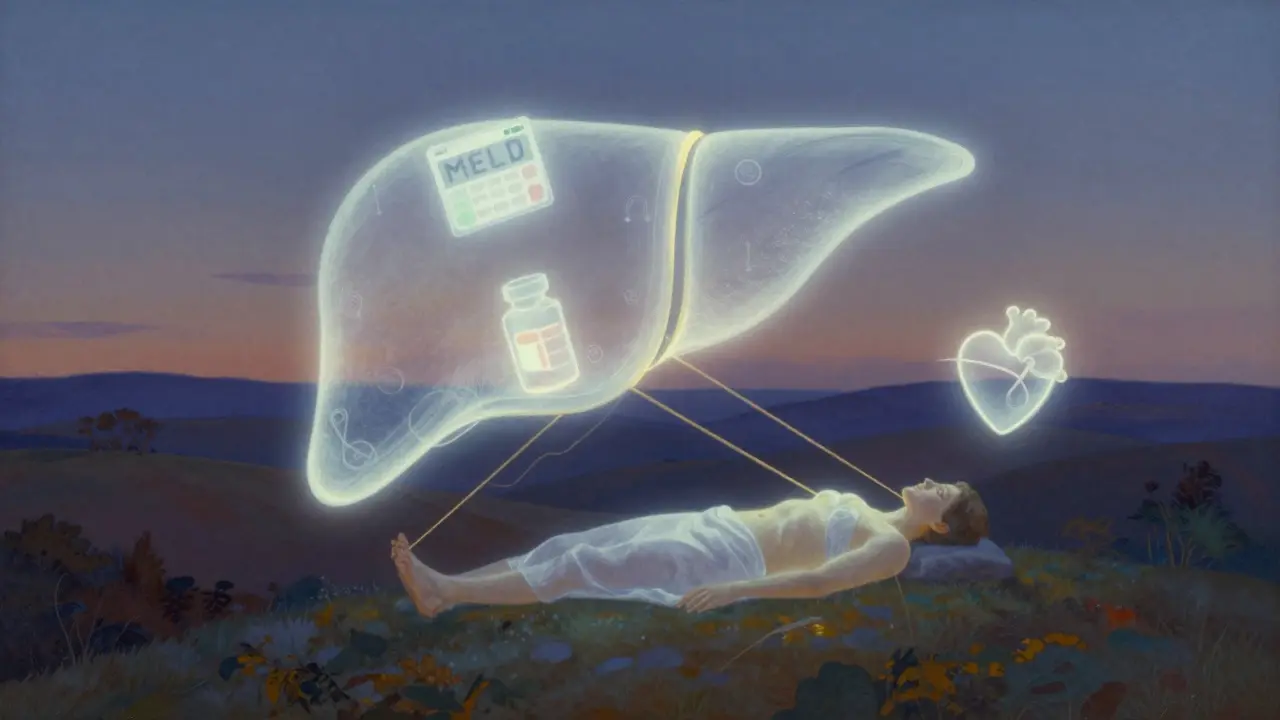

When your liver fails, there’s no backup system. No second chance. No workaround. For thousands of people each year, liver transplantation is the only path back to life. It’s not a simple fix-it’s a complex, high-stakes journey that begins long before the operating room and lasts a lifetime. This isn’t just about swapping an organ. It’s about meeting strict medical criteria, surviving a major surgery, and managing a lifelong drug regimen to keep your new liver alive.

Who Gets a Liver Transplant?

Not everyone with liver disease qualifies. The system is designed to give the organ to those who need it most and have the best chance of surviving. The Model for End-Stage Liver Disease, or MELD score, is the key. It’s calculated using three blood tests: bilirubin, creatinine, and INR. Scores range from 6 to 40. The higher your score, the sicker you are-and the higher your priority on the waiting list. A MELD score of 25 or above means you’re in critical condition. People with scores below 15 rarely get offered a liver unless they have liver cancer. For liver cancer patients, the rules are even tighter. You must meet the Milan criteria: one tumor no bigger than 5 cm, or up to three tumors, each under 3 cm, with no spread to blood vessels. If your alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) level is above 1,000 and doesn’t drop after treatment, you’re typically ineligible unless your case goes through a special review. But medical fitness isn’t enough. You also need to pass a psychosocial evaluation. This means proving you have stable housing, reliable transportation, and a support system. If you’ve struggled with alcohol or drugs, you’ll need to show at least six months of sobriety. Some centers are starting to question this rule-studies show people with three months of abstinence have similar survival rates. But most still require six months. Insurance companies often deny coverage for the pre-transplant workup, which can cost thousands. That’s a major barrier for many. Living donors add another layer. They must be between 18 and 55, have a BMI under 30, and be free of liver, heart, lung, or kidney disease. They can’t smoke or use drugs or alcohol. Their liver must be healthy enough to regrow after giving up 55-70% of it. The remnant liver must be at least 35% of the original volume. The graft-to-recipient weight ratio must be at least 0.8%. These numbers aren’t arbitrary-they’re based on decades of survival data.The Surgery: What Happens in the Operating Room

A liver transplant takes between six and twelve hours. Most surgeons use the piggyback technique-leaving the recipient’s inferior vena cava intact. This reduces blood loss and lowers the risk of complications. The surgery has three phases. First, the diseased liver is removed (hepatectomy). Then comes the anhepatic phase-when the body has no liver at all. This is the most dangerous part. Blood pressure drops, fluids shift, and the body struggles to maintain balance. Finally, the donor liver is stitched in. Blood vessels and bile ducts are reconnected. For living donor transplants, surgeons remove the right lobe (about 60% of the liver) for adult recipients. For children, they take the left lateral segment. The donor’s liver regrows to full size in about six to eight weeks. The recipient’s new liver starts working almost immediately. That’s one of the biggest advantages of living donation: no waiting. While deceased donor waits can stretch to over a year, especially in high-MELD patients in California, living donor transplants can happen within three months. But it’s not risk-free. Donors face a 0.2% chance of dying during surgery. About 20-30% experience complications-bile leaks, infections, or pain that lasts months. Still, most donors say it was worth it. One 58-year-old donor in the U.S., slightly over the age limit, was approved after his liver anatomy was found to be unusually strong. His case was rare, but it showed that rigid rules can bend when the science supports it. Post-op care starts in the ICU. You’ll stay there for five to seven days. Total hospital time is usually two to three weeks. You’ll be on a ventilator at first, then slowly weaned off. Pain is managed with IV meds. Nurses watch your urine output, blood pressure, and liver enzymes like a hawk. Rejection can happen within days. That’s why you’ll get blood tests every single day.

Immunosuppression: The Lifelong Drug Regimen

Your new liver is a foreign object. Your immune system will try to kill it. That’s why you need immunosuppressants-drugs that silence your body’s defense system. The standard starting point is triple therapy: tacrolimus, mycophenolate mofetil, and prednisone. Tacrolimus is the backbone. You’ll need blood tests to keep its level between 5-10 ng/mL in the first year, then 4-8 ng/mL after that. Too low, and your body rejects the liver. Too high, and you risk kidney damage, nerve problems, or diabetes. About 35% of patients develop kidney issues by year five. One in four gets diabetes. One in five has tremors or headaches. Mycophenolate helps block immune cells. But it causes nausea, diarrhea, and low blood counts. About 30% of patients stop taking it because of stomach problems. Ten percent get anemia or low white blood cells. Prednisone, a steroid, was once a must. But now, 45% of U.S. transplant centers skip it after the first month. Why? Because it causes weight gain, bone loss, and diabetes. Removing it cuts diabetes risk from 28% to 17%. Some patients get induction therapy before surgery. Low-risk patients get basiliximab. High-risk patients get anti-thymocyte globulin. These are strong drugs given in the hospital over several days. They help prevent early rejection. About 15% of patients have acute rejection in the first year. It’s often caught early through blood tests. Treatment? Increase tacrolimus or add sirolimus. Most respond well. But chronic rejection is harder to treat. That’s why lifelong monitoring is non-negotiable.What Comes After: The Daily Reality

The first three months are intense. You’ll go to the clinic weekly for blood tests. Months four to six: biweekly. After that, monthly. Year two and beyond: quarterly. You’ll need to track every pill. Miss one dose, and rejection risk jumps. Studies show you need at least 95% adherence to avoid failure. You’ll also learn to spot warning signs: fever over 100.4°F, yellow skin, dark urine, fatigue, or abdominal swelling. Call your team immediately. Infections are a major threat. You can’t be around sick people. No crowded places. No raw sushi. No gardening without gloves. You’ll need vaccines-but not live ones. Flu shots? Yes. MMR? No. Medication costs are high. $25,000 to $30,000 a year, on average, just for the drugs. That’s not counting doctor visits, labs, or hospital stays. Insurance coverage varies wildly. Some patients lose coverage after a year. Others fight for years to get it approved. Geographic disparities are real. In the Midwest, a patient with a MELD score of 25-30 waits about eight months. In California, it’s 18 months. The system is unfair. Some centers have dedicated transplant coordinators. Those centers have 87% one-year survival. Centers without them? 82%. That difference saves lives.

Evan Smith

January 8, 2026 AT 13:35So let me get this straight-you’re telling me I can give away 60% of my liver and walk away with a story to tell at BBQs? And the recipient gets a new lease on life? Man, I’d do it tomorrow if I wasn’t allergic to surgery and had a spare liver lying around.

Joanna Brancewicz

January 10, 2026 AT 00:52MELD score thresholds are clinically sound, but the psychosocial criteria? Arbitrary. Six months sobriety isn’t evidence-based-it’s a relic. We’re denying transplants to people who could thrive with harm reduction, not abstinence-only dogma.

Lois Li

January 10, 2026 AT 13:26I’ve seen family members go through this. The daily pill schedule is brutal. You forget one dose and you’re panic-checking your liver enzymes like a gamer watching their health bar. And the cost? I know someone who lost insurance after a year and had to sell her car just to afford tacrolimus.

No one talks about how lonely it is being immunocompromised. You can’t hug your grandkids when they’re sick. You can’t go to the mall. You become a ghost in your own life.

christy lianto

January 10, 2026 AT 23:08They say survival rates are 85% after one year-that’s amazing. But what about the 15% who don’t make it? And what about the ones who survive but are trapped in a cycle of kidney damage, diabetes, and tremors because of the meds? This isn’t a miracle. It’s a trade-off. And we’re selling it like it’s a vacation.

Kristina Felixita

January 12, 2026 AT 10:08Living donor transplants are the real MVPs!! No waiting, liver starts working IMMEDIATELY, and the donor gets to feel like a superhero?? I know a guy who donated to his sister-he said the recovery hurt, but seeing her eat pizza again? Worth every second. We need more awareness, like, TODAY.

Luke Crump

January 13, 2026 AT 08:45So we’re giving people new livers… but making them take drugs that turn them into diabetic, kidney-failing zombies? That’s not medicine. That’s a Faustian bargain with Big Pharma. The real solution? Stop letting corporations control organ allocation and drug pricing. Let the liver breathe-without the chemical leash.

Aubrey Mallory

January 14, 2026 AT 05:32Anyone who says the six-month sobriety rule is outdated hasn’t seen the data. Relapse rates are higher in those who get transplants too early. This isn’t about punishment-it’s about survival. We’re not handing out free organs to people who’ll abuse them again.

And if you can’t afford the meds? That’s a systemic failure, not a transplant failure. Fix the healthcare system, not the criteria.

Dave Old-Wolf

January 14, 2026 AT 16:15I’m curious-how many of those living donors end up regretting it? I know the stats say most say it was worth it, but what about the quiet ones? The ones who still have chronic pain, or can’t lift their kids anymore? Are we asking them enough about quality of life after?

Prakash Sharma

January 15, 2026 AT 11:05In India, liver transplant is a luxury. You need connections, not just a MELD score. But I’ve seen people die waiting because they can’t afford $50k. The system here is broken too-but we don’t have the tech or the money to fix it. So we just pray.